Ending the Captagon Trade in Syria?

February 10, 2026 - Written by Ria Uppal

Introduction

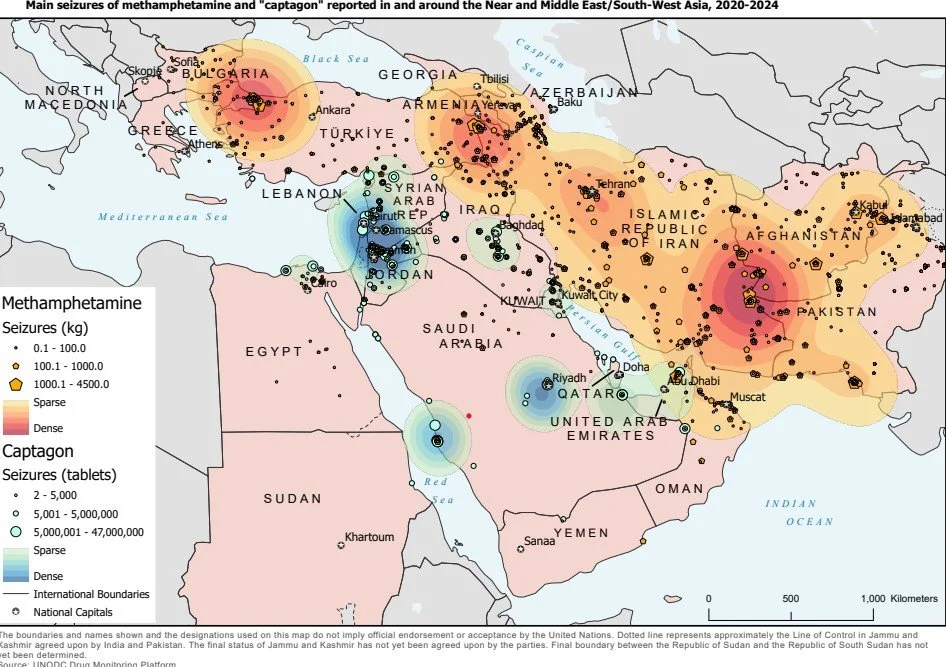

Since the Arab Spring and Syria’s Civil War in 2011, the political trajectory of the Syrian government has been warped by the actions of Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorial regime. Despite his ousting in December 2024, the regime marked over two decades of political, economic and geopolitical instability and since has reformed the interactions between Syria and the surrounding Arab states. The Assad regime has been characterised by the lethal use of force, chemical weapons, and perpetual violence against its own citizens, but also its significant involvement in the Fenethylline (Captagon) trade. Since Assad’s exit from power in late 2024, Syria remains a global hub for the production and distribution of Captagon, suggesting that the involvement of the drug as a stimulator of Syria’s economy still holds prevalence in the Arab world.

Captagon is the commercial name for a highly addictive, synthetic and mass produced amphetamine that has been widely distributed across the Middle East for decades. It originates from 1960’s Germany, from the pharmaceutical company Degussa Pharma Gruppe, where it was mainly prescribed to treat attention deficit disorder and narcolepsy. In 1986, Captagon was considered by the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances to be detrimental with severe side effects, and as such was banned and production discontinued. However, as official production ceased, counterfeit Captagon was produced and smuggled out of Bulgaria in the 1990’s, via Balkan and Turkish criminal networks, eventually finding its way into the Arab Peninsula. By the early 2000’s, Captagon had established itself in Lebanon and by the mid-2000’s, settled in Syria. The production and circulation of Captagon in Syria and within the Gulf was worth an estimated $3.4 billion in 2020, and over $10 billion at its pinnacle.

Contextual Analysis

Amidst sanctions, declining GDP, lack of economic infrastructure and diplomatic isolation, Assad was quietly turning Captagon, a 10 billion dollar trade, into a strategic asset. Syria’s Fourth Armoured Division led by brother Maher al-Assad, Military Intelligence Directorate and National Defence Forces, along with regime-aligned actors, have been key players in the perpetuation of the drug both within Syria and cross-border.

In 2020, 84 million Captagon pills were seized from the port of Salermo, Italy, confirming what policy specialists had already known; that Syria was a major player in the production and exportation of this drug, with direct control of approximately 7.3 billion dollars worth of Captagon revenues.

For 24 years, Captagon has existed as a state-enabled illicit stream of revenue to finance and facilitate the Assad regime, its dictatorial pursuits, and to sustain it in the way of circumventing economic distress. Consequently, Assad had little interest in losing the income and benefits afforded to its patronage network by Captagon, nor did it intend to stem the flow in a meaningful way conducive to encouraging social, economic or political stability.

By the time Assad made his appearance at the first Arab League Summit since 2011, Captagon had already seeped into Jordan and onto the lucrative Gulf markets. From 2020-2023 the Jordanian army had dealt with over 1700 smuggling and infiltration attempts, causing frenzy within Jordanian society and a domestic drug problem. Across the Arabian Peninsula, Saudi Arabia accounts for approximately 50% of global Captagon consumption, with a record number of seizing 46 million pills in 2022. In April 2022, the Jordanian authorities seized 17 million pills and in 2021, 15.5 million along its border with Syria. Coincidental with the seizure in Italy, 95 million tablets had been smuggled to Malaysia and 74 kilograms worth of the drug in Nigeria.

Key Stakeholders post-Assad

Jordan

Jordan serves as a critical transit corridor for Captagon distribution. It fared the worst of changes to regional geopolitics and had experienced cycles of disengagement with Syria. The bust in 2022 resulted in Jordan leading the push towards normalisation of relations between the Arab League and Syria, in an attempt to centre the Captagon trade as a credible tool for diplomacy and reengagement.

However, Jordan’s diplomatic endeavours failed. The reality was that the Assad regime had little interest in losing the income and financial benefits afforded by Captagon. As a result, Jordanian military response to trafficking along borderlands is a shoot-to-kill policy and going even further to launch airstrikes along the Syria-Lebanon border, further emphasising the trade as a national and regional security threat.

Saudi Arabia & Gulf States

Despite the Gulf leaders’ protests against the trade, those states themselves do not have clean hands. In addition to Saudi Arabia accounting for approximately 50% of global consumption, Gulf Cooperation Council states emerged as the main consumer markets of Captagon and account for almost 90% of the regional market. Saudi Arabia accounted for approximately 570,000 worth of seized pills from 2016-2023, whilst the United Arab Emirates, and Lebanon accounted for approximately 200,000, and 120,000 pills respectively. With a Saudi tip-off provided by the Ministry of Interior, Lebanese authorities dismantled an illegal stronghold in 29th January 2026 in the Baalbek region, seizing 820 pills, hashish, and weapons, amongst other items. Saudi forces are keen to engage in the necessary intelligence collaboration across borders to prevent further expansion of the trade and reduce trafficking attempts.

Lebanon

Lebanon provided ideal circumstances for circulating the drug; it is undermined by Hezbollah and ethnic factions with large refugee populations, leading to an inherently unstable political climate. So much Captagon has been smuggled from Lebanon into Saudi Arabia that in 2021, Saudi widened their confrontations with Iran by suspending all Lebanese fresh produce, as this is where Captagon was smuggled within, adding to Lebanon’s critical economic issues and drug problems. Alongside the decline of Syria’s civil conflict in the years leading up to Assad’s ousting, Captagon trafficking in Lebanon has exponentially increased. The utilisation of the Beqaa Valley as a trade route, previously in growing and transporting hashish, has now transformed into an unregulated region ideal for smuggling Captagon through. Beqaa Valley hosts various political, criminal, indigenous clan-based factions and terrorist groups such as Hezbollah that facilitate the flow of Captagon through the valley itself and into Lebanon and its neighbouring countries.

Hezbollah

Reports strongly indicated Hezbollah's engagement with the Captagon trade, on both a transitory level and a production level. The observation is that large-scale production and smuggling occurs in Hezbollah-controlled regions and that it would be near to impossible for this to be facilitated without their engagement and enablement.

One of the primary Captagon production and transit zones are in the Hermel-Baalbek regions of the northern portion of the Beqaa Valley, where Hezbollah holds significant influence. As a result, the militant group earns hundreds of millions of dollars annually from the Captagon trade, using it to finance military and political operations.

Iraq

Iraq is swiftly emerging as a new major player in the Captagon trade. From 2019-2024 has experienced a dramatic surge in trafficking and consumption, not just of “old-school” substances such as hashish, heroin and methamphetamine, but also of Captagon.

The legacy of conflict that has occurred in Iraq has created an environment conducive to trafficking, production and distribution of drugs, but the surge in Captagon trafficking along the Syria-Iraq border has solidified Iraq’s position as a critical conduit connecting major producers.

In July 2023, Iraqi authorities uncovered the first Captagon laboratory in Muthanna province, close to the Saudi border. In April 2025, Iraqi authorities also seized 30,000 Captagon pills close to the Syrian border, near al-Bhaguz, highlighting increased activity related to trafficking, smuggling and production. Parallel to this development, Captagon consumption within Iraq itself has become rife.

Captagon post-Assad

Throughout 2024, the new administration of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) under Al-Sharaa orchestrated the seizure of 200 million Captagon pills over a span of four months, almost twenty times what Assad achieved. These seizures not only occurred in local strongholds, but in locations previously protected by the former administration such as warehouses owned by Maher al-Assad and other regime aligned criminal network locations. On the 7th January 2026, Syrian authorities seized nearly 500,000 pills in Hama, Syria, hidden inside specially designed iron pipes for smuggling purposes.

The disruption in the Captagon trade orchestrated by HTS, is laid out in a dual phased approach. Phase One concentrates on dismantling the physical infrastructures of production; from December 2024 to September 2025, HTS uncovered 7 large scale laboratories, 23 warehouses and other storage facilities and stockpiles. Phase Two concentrates on disrupting trafficking networks by way of expanding intelligence collection and cross-border coordination. Following the implementation of Phase Two, there was an increase in arrests of prominent regime-era producers, both inside and outside Syrian territories. These insights further highlight the regime’s half-hearted approach to stalling Captagon production and maintaining the transit-state narrative. Aligning with the shift in illicit smuggling activity along Syria’s borders, implementation of Phase Two activities have occurred in networks along the Syria-Jordan and Syria-Lebanon borders, combatting operations orchestrated by local tribes and militias.

In maintaining the narrative that Syria was merely a transitory measure for Captagon, the Assad regime never announced any plans to shut down production facilities. However in the first four months of HTS in power, at least nine production facilities have been seized. The upward trajectory in the competency, frequency and success of post-Assad regime raids only highlights the regime’s lacklustre approach towards impactfully destabilising the Captagon trade, and Assad’s desire to continue benefitting from it, whatever the costs.

Furthermore, there has also been significant financial investment from GCC states - namely Saudi Arabia - with the Saudi government settling $15.5million worth of Syria’s debt to the World Bank, subsequently allowing it to lend a further $146 million dollar grant to Syria in March 2025.

More significantly has been the role of Saudi Arabia and Türkiye in influencing western allies to lift sanctions that were initially imposed during the Assad Regime. After welcoming al-Sharaa to the Whitehouse in November 2025, the US declared partial removal of sanctions upon Syria.

In a lateral move, Qatar has pledged to fund Syria’s public sector and double its electricity supply, offering a critical lifeline to the new government. On the 4th February, Syria signed a deal brokered by US Special Envoy Tom Barrack, with Chevron Oil and Qatari Power International Holdings, to strengthen partnerships in the energy sector and further reinforcing its commitment to broadening relations with major powers in a way that is mutually beneficial and also boosts economic revenue.

The GCC’s continued engagement with rebuilding Syria serves as a positive trajectory for HTS’ continued efforts in stabilising the Captagon trade; increased economic stability will hopefully provide a portion of the necessary cash flow required to rebuild infrastructures, subsequently reducing reliance upon illicit trade.

Opportunities & Risks

In light of HTS’ dual-phase approach, there has been an emergence of opportunities created for non-state actors to fill the power vacuum that Assad’s exit has resulted in.

The state monopoly that Syria once possessed on the Captagon trade has been steadfastly transformed into a form of non-state entrepenurialism, lying in the hands of warlords, tribes, terrorist groups and prominent families. The opening has been utilised by non-state actors to exploit the evolving market. This presents a number of risks for regional dynamics and new government;

The Captagon trade and its effects are far more uncontrollable in the hands of scattered non-state actors than in the hands of government, presenting a challenge that cannot be confronted in the form regional and governmental diplomacy with those involved.

A trade handled by threatening non-state actors becomes less of a geopolitical tool for negotiations and more of a regional drug problem, causing strain on economies and damaging swathes of people in societies.

Captagon trade in the hands of non state actors, particularly militia, has the ability to generate new means of financing clandestine pursuits such as re-establishing formerly disrupted trade routes, enhancing military hardware and acquiring weapons, further reinforcing their leverage as threatening non-state actors with a significant amount of influence.

A trade handled by threatening non-state actors also means that the economic rebate that Captagon previously provided no longer exists, because government does not partake in active intervention within the market and its dynamics.

Post-regime Captagon trade has not only had a spillover effect into contested borderlands and conflict affected areas, but combined with its more prominent association with threatening non-state actors, this enables continued Captagon production with reduced risk and increased proximity to destination markets.

HTS have consistently rejected Syria as an anchor of Captagon production due to their conservative ideology but also due to knowing that the usage of the Captagon trade attracted international condemnation and economic sanctions. Their dual-phase approach is representative to the opportunistic manner in which they intend to take a hold of the trade and placate it as much as possible. The hopeful success of this in the future, depicts HTS as a reliable government not just to other regional powers, but to the rest of the international community.

In the immediate aftermath of Assad’s exit, HTS was unable to maximise their approach due to lacking political legitimacy, however, as they incrementally consolidated authority, the Interior Minister was able to pursue more ambitious operations against criminal elites aligned with the former regime. Along with the huge raids that have occurred at the beginning of 2026, HTS have several opportunities which they are able to act upon;

There is an outstanding opportunity to continue to present themselves as a collaborative and reliable regime with a long-term vision for creating peace and stability within the region.

HTS’ open declaration of destroying the Captagon industry, could potentially prompt regional collaboration with Saudi Arabia and Jordan; they are still suffering from the economic and social effects of the trade and would benefit from a decline in Captagon exports within their own societies and borderlands. There is an opportunity for incentivisation through sanctions, trade benefits and intelligence-sharing agreements.

The UK and American government’s decision in early 2025 to remove HTS as a previously designated terrorist organisation, allows for closer western engagement with the new Syrian government. This may also include humanitarian aid, removal of sanctions and tariffs, and further resources to combat the captagon trade.

Conclusion

The Captagon trade has been instrumental to the Syrian economy for the past 24 years and so dismantling it is no easy feat; it requires a certain level of economic stability to reinforce Syria, for government to be able to execute in any meaningful capacity. HTS’ dual-phase approach attempts to dismantle the trade at a systemic and logistical level as opposed to the shallow and purposefully futile whack-a-mole approach that was previously implemented in the Assad regime. This is a welcome change when placing HTS’ pursuits in the geopolitical context of regional and international implications of the Captagon trade.

The trade is fundamental to re-stabilising not just Syria but pockets within the whole region and so it should be central to diplomatic and economic efforts. The current situation in Syria is one of development; these huge transformations will not happen overnight but it is clear that the new government is committed to imploring new international relationships and deepening existing ones in order to combat a trade that has destroyed its economy and weakened geopolitical ties in the region This will be the foundation of its predicted success.

Written by Ria Uppal

Analyst on the Security & Terrorism Research Desk